-

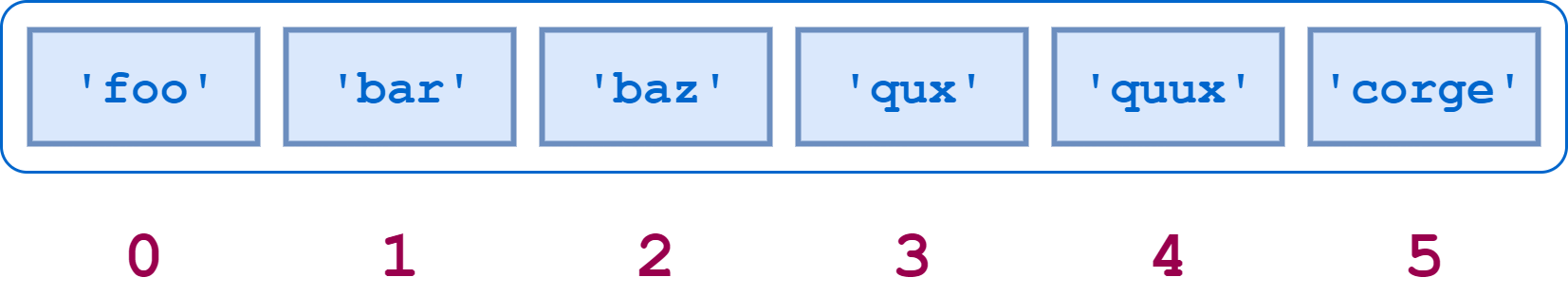

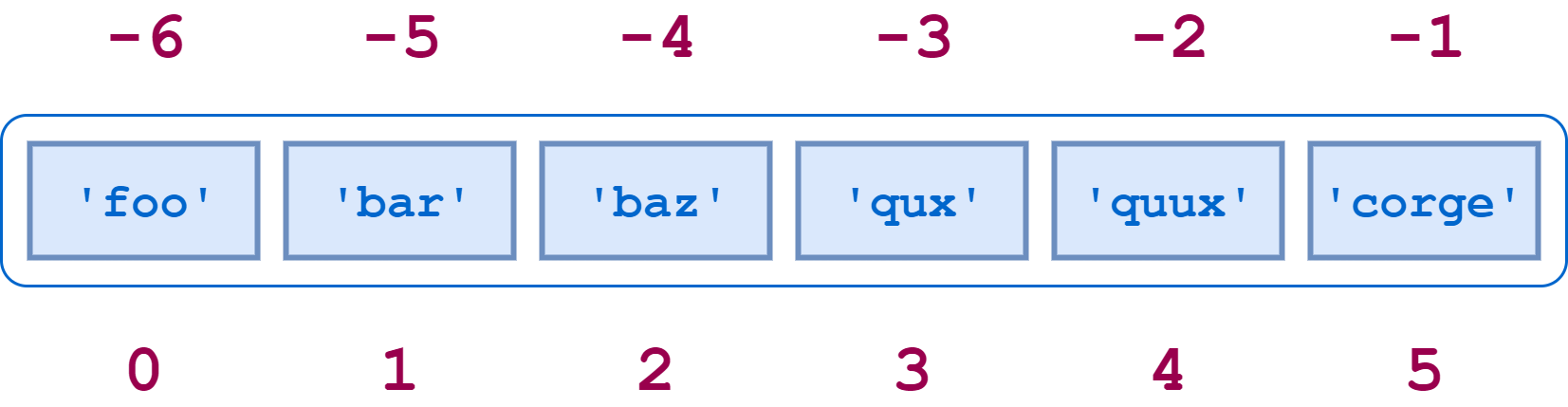

>>> a[-5:-2] [‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘] >>> a[1:4] [‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘] >>> a[-5:-2] == a[1:4] True -

Omitting the first index starts the slice at the beginning of the list, and omitting the second index extends the slice to the end of the list:省略起止索引数时表示什么?

-

>>> print(a[:4], a[0:4]) [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘] [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘] >>> print(a[2:], a[2:len(a)]) [‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] [‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> a[:4] + a[4:] [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> a[:4] + a[4:] == a True -

You can specify a stride跨度—either positive or negative:

-

>>> a[0:6:2] [‘foo‘, ‘baz‘, ‘quux‘] >>> a[1:6:2] [‘bar‘, ‘qux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> a[6:0:-2] [‘corge‘, ‘qux‘, ‘bar‘] -

The syntax for reversing a list逆序 works the same way it does for strings:

-

>>> a[::-1] [‘corge‘, ‘quux‘, ‘qux‘, ‘baz‘, ‘bar‘, ‘foo‘] -

The

[:]syntax works for lists从头至尾. However, there is an important difference between how this operation works with a list and how it works with a string.If

sis a string,s[:]returns a reference to the same object:

>>> s = ‘foobar‘

>>> s[:]

‘foobar‘

>>> s[:] is s

True

Conversely, if a is a list, a[:] returns a new object that is a copy of a:该切片形式返回一个新的列表

-

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> a[:] [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> a[:] is a False

Several Python operators and built-in functions can also be used with lists in ways that are analogous to strings:

-

The

inandnot inoperators: -

>>> a [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> ‘qux‘ in a

成员运算符可用

True >>> ‘thud‘ not in a True -

The concatenation (

+) and replication (*) operators:可以加和乘,与字符串类似 -

>>> a [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> a + [‘grault‘, ‘garply‘] [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘, ‘garply‘] >>> a * 2 [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] -

The

len(),min(), andmax()functions:

-

>>> a [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘] >>> len(a) 6 >>> min(a) ‘bar‘ >>> max(a) ‘qux‘

It’s not an accident that strings and lists behave so similarly. They are both special cases of a more general object type called an iterable, which you will encounter in more detail in the upcoming tutorial on definite iteration.

By the way, in each example above, the list is always assigned to a variable before an operation is performed on it. But you can operate on a list literal as well:

>>> [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘][2]

‘baz‘

>>> [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘][::-1]

[‘corge‘, ‘quux‘, ‘qux‘, ‘baz‘, ‘bar‘, ‘foo‘]

>>> ‘quux‘ in [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

True

>>> [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘] + [‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> len([‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘][::-1])

6

For that matter, you can do likewise with a string literal:

>>> ‘If Comrade Napoleon says it, it must be right.‘[::-1]

‘.thgir eb tsum ti ,ti syas noelopaN edarmoC fI‘

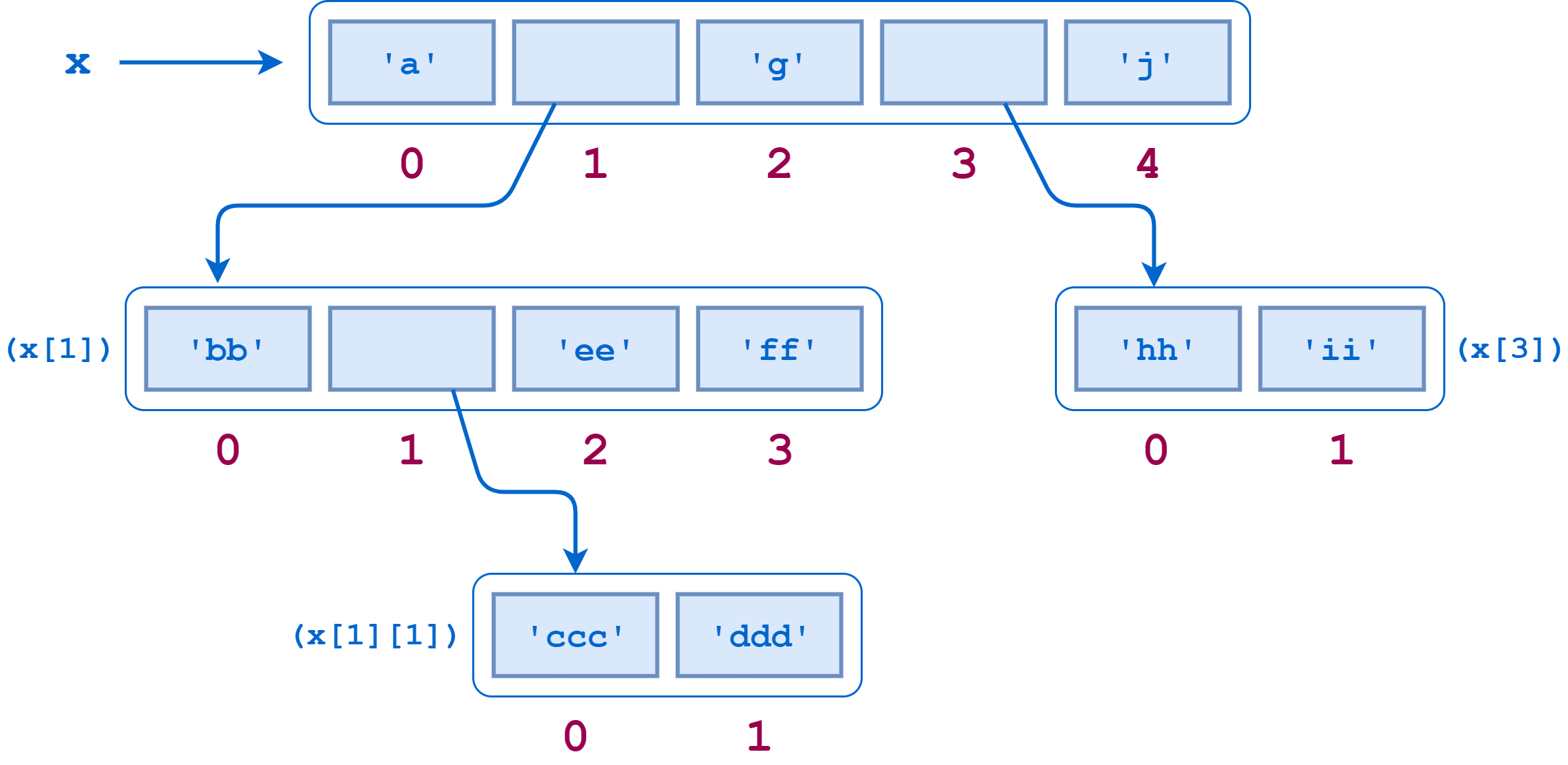

Lists Can Be Nested(可嵌套)

You have seen that an element in a list can be any sort of object. That includes another list. A list can contain sublists, which in turn can contain sublists themselves, and so on to arbitrary depth.

Consider this (admittedly contrived) example:

>>> x = [‘a‘, [‘bb‘, [‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘, ‘ff‘], ‘g‘, [‘hh‘, ‘ii‘], ‘j‘]

>>> x

[‘a‘, [‘bb‘, [‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘, ‘ff‘], ‘g‘, [‘hh‘, ‘ii‘], ‘j‘]

The object structure that x references is diagrammed below:涉及到拷贝

A Nested List

A Nested List

x[0], x[2], and x[4] are strings, each one character long:

>>> print(x[0], x[2], x[4])

a g j

But x[1] and x[3] are sublists:

>>> x[1]

[‘bb‘, [‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘, ‘ff‘]

>>> x[3]

[‘hh‘, ‘ii‘]

To access the items in a sublist, simply append an additional index:索引也是根据嵌套来的

>>> x[1]

[‘bb‘, [‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘, ‘ff‘]

>>> x[1][0]

‘bb‘

>>> x[1][1]

[‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘]

>>> x[1][2]

‘ee‘

>>> x[1][3]

‘ff‘

>>> x[3]

[‘hh‘, ‘ii‘]

>>> print(x[3][0], x[3][1])

hh ii

x[1][1] is yet another sublist, so adding one more index accesses its elements:

>>> x[1][1]

[‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘]

>>> print(x[1][1][0], x[1][1][1])

ccc ddd

There is no limit, short of the extent of your computer’s memory, to the depth or complexity with which lists can be nested in this way.

All the usual syntax regarding indices and slicing applies to sublists as well:

>>> x[1][1][-1]

‘ddd‘

>>> x[1][1:3]

[[‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘]

>>> x[3][::-1]

[‘ii‘, ‘hh‘]

However, be aware that operators and functions apply to only the list at the level you specify and are not recursive(操作和函数在你指定的工作层不是递归的,即只涉及本层). Consider what happens when you query the length of x using len():

>>> x

[‘a‘, [‘bb‘, [‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘, ‘ff‘], ‘g‘, [‘hh‘, ‘ii‘], ‘j‘]

>>> len(x)

5

>>> x[0]

‘a‘

>>> x[1]

[‘bb‘, [‘ccc‘, ‘ddd‘], ‘ee‘, ‘ff‘]

>>> x[2]

‘g‘

>>> x[3]

[‘hh‘, ‘ii‘]

>>> x[4]

‘j‘

x has only five elements—three strings and two sublists. The individual elements in the sublists don’t count toward x’s length.

You’d encounter a similar situation when using the in operator:

>>> ‘ddd‘ in x

False

>>> ‘ddd‘ in x[1]

False

>>> ‘ddd‘ in x[1][1]

True

‘ddd‘ is not one of the elements in x or x[1]. It is only directly an element in the sublist x[1][1]. An individual element in a sublist does not count as an element of the parent list(s).

Lists Are Mutable(列表是可修改的)

Most of the data types you have encountered so far have been atomic types. Integer or float objects, for example, are primitive units that can’t be further broken down. These types are immutable, meaning that they can’t be changed once they have been assigned. It doesn’t make much sense to think of changing the value of an integer. If you want a different integer, you just assign a different one.

By contrast, the string type is a composite type. Strings are reducible to smaller parts—the component characters. It might make sense to think of changing the characters in a string. But you can’t. In Python, strings are also immutable.

The list is the first mutable data type you have encountered. Once a list has been created, elements can be added, deleted, shifted, and moved around at will. Python provides a wide range of ways to modify lists.

Modifying a Single List Value(修改单个值)

A single value in a list can be replaced by indexing and simple assignment:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a[2] = 10

>>> a[-1] = 20

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, 10, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, 20]

You may recall from the tutorial Strings and Character Data in Python that you can’t do this with a string:(字符串是不可修改的)

>>> s = ‘foobarbaz‘

>>> s[2] = ‘x‘

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: ‘str‘ object does not support item assignment

A list item can be deleted with the del command:(列表元素还可以删除)

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> del a[3]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

Modifying Multiple List Values(还可以修改多个值)

What if you want to change several contiguous elements in a list at one time? Python allows this with slice assignment, which has the following syntax:

a[m:n] = <iterable>

Again, for the moment, think of an iterable as a list. This assignment replaces the specified slice of a with <iterable>:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a[1:4]

[‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘]

>>> a[1:4] = [1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, 5.5]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, 1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, 5.5, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a[1:6]

[1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, 5.5]

>>> a[1:6] = [‘Bark!‘]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘Bark!‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

The number of elements inserted need not be equal to the number replaced. Python just grows or shrinks the list as needed.

You can insert multiple elements in place of a single element—just use a slice that denotes only one element:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a[1:2] = [2.1, 2.2, 2.3]

>>> a

[1, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 3]

Note that this is not the same as replacing the single element with a list:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a[1] = [2.1, 2.2, 2.3]

>>> a

[1, [2.1, 2.2, 2.3], 3]

You can also insert elements into a list without removing anything. Simply specify a slice of the form [n:n] (a zero-length slice) at the desired index:

>>> a = [1, 2, 7, 8]

>>> a[2:2] = [3, 4, 5, 6]

>>> a

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

You can delete multiple elements out of the middle of a list by assigning the appropriate slice to an empty list. You can also use the del statement with the same slice:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a[1:5] = []

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> del a[1:5]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘corge‘]

Prepending or Appending Items to a List(在列表前后增加元素)

Additional items can be added to the start or end of a list using the + concatenation operator or the += augmented assignment operator:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a += [‘grault‘, ‘garply‘]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, ‘grault‘, ‘garply‘]

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a = [10, 20] + a

>>> a

[10, 20, ‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

Note that a list must be concatenated with another list, so if you want to add only one element, you need to specify it as a singleton list:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a += 20

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#58>", line 1, in <module>

a += 20

TypeError: ‘int‘ object is not iterable

>>> a += [20]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, 20]

Note: Technically, it isn’t quite correct to say a list must be concatenated with another list. More precisely, a list must be concatenated with an object that is iterable. Of course, lists are iterable, so it works to concatenate a list with another list.

Strings are iterable also. But watch what happens when you concatenate a string onto a list:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘]

>>> a += ‘corge‘

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘c‘, ‘o‘, ‘r‘, ‘g‘, ‘e‘]

This result is perhaps not quite what you expected. When a string is iterated through, the result is a list of its component characters. In the above example, what gets concatenated onto list a is a list of the characters in the string ‘corge‘.

If you really want to add just the single string ‘corge‘ to the end of the list, you need to specify it as a singleton list:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘]

>>> a += [‘corge‘]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

If this seems mysterious, don’t fret too much. You’ll learn about the ins and outs of iterables in the tutorial on definite iteration.

Methods That Modify a List

Finally, Python supplies several built-in methods that can be used to modify lists. Information on these methods is detailed below.

Note: The string methods you saw in the previous tutorial did not modify the target string directly. That is because strings are immutable. Instead, string methods return a new string object that is modified as directed by the method. They leave the original target string unchanged:

>>> s = ‘foobar‘

>>> t = s.upper()

>>> print(s, t)

foobar FOOBAR

List methods are different. Because lists are mutable, the list methods shown here modify the target list in place.

a.append(<obj>)

Appends an object to a list.

a.append(<obj>) appends object <obj> to the end of list a:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> a.append(123)

>>> a

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, 123]

Remember, list methods modify the target list in place. They do not return a new list:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> x = a.append(123)

>>> print(x)

None

>>> a

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, 123]

Remember that when the + operator is used to concatenate to a list, if the target operand is an iterable, then its elements are broken out and appended to the list individually:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> a + [1, 2, 3]

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, 1, 2, 3]

The .append() method does not work that way! If an iterable is appended to a list with .append(), it is added as a single object:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> a.append([1, 2, 3])

>>> a

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, [1, 2, 3]]

Thus, with .append(), you can append a string as a single entity:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> a.append(‘foo‘)

>>> a

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, ‘foo‘]

a.extend(<iterable>)

Extends a list with the objects from an iterable.

Yes, this is probably what you think it is. .extend() also adds to the end of a list, but the argument is expected to be an iterable. The items in <iterable> are added individually:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> a.extend([1, 2, 3])

>>> a

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, 1, 2, 3]

In other words, .extend() behaves like the + operator. More precisely, since it modifies the list in place, it behaves like the += operator:

>>> a = [‘a‘, ‘b‘]

>>> a += [1, 2, 3]

>>> a

[‘a‘, ‘b‘, 1, 2, 3]

a.insert(<index>, <obj>)

Inserts an object into a list.

a.insert(<index>, <obj>) inserts object <obj> into list a at the specified <index>. Following the method call, a[<index>] is <obj>, and the remaining list elements are pushed to the right:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a.insert(3, 3.14159)

>>> a[3]

3.14159

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, 3.14159, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

a.remove(<obj>)

Removes an object from a list.

a.remove(<obj>) removes object <obj> from list a. If <obj> isn’t in a, an exception is raised:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a.remove(‘baz‘)

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a.remove(‘Bark!‘)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#13>", line 1, in <module>

a.remove(‘Bark!‘)

ValueError: list.remove(x): x not in list

a.pop(index=-1)

Removes an element from a list.

This method differs from .remove() in two ways:

- You specify the index of the item to remove, rather than the object itself.

- The method returns a value: the item that was removed.

a.pop() simply removes the last item in the list:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a.pop()

‘corge‘

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘]

>>> a.pop()

‘quux‘

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘]

If the optional <index> parameter is specified, the item at that index is removed and returned. <index> may be negative, as with string and list indexing:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a.pop(1)

‘bar‘

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a.pop(-3)

‘qux‘

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘baz‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

<index> defaults to -1, so a.pop(-1) is equivalent to a.pop().

Lists Are Dynamic

This tutorial began with a list of six defining characteristics of Python lists. The last one is that lists are dynamic. You have seen many examples of this in the sections above. When items are added to a list, it grows as needed:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a[2:2] = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a += [3.14159]

>>> a

[‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, 1, 2, 3, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘, 3.14159]

Similarly, a list shrinks to accommodate the removal of items:

>>> a = [‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

>>> a[2:3] = []

>>> del a[0]

>>> a

[‘bar‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘]

Python Tuples

Python provides another type that is an ordered collection of objects, called a tuple.

Pronunciation varies depending on whom you ask. Some pronounce it as though it were spelled “too-ple” (rhyming with “Mott the Hoople”), and others as though it were spelled “tup-ple” (rhyming with “supple”). My inclination is the latter, since it presumably derives from the same origin as “quintuple,” “sextuple,” “octuple,” and so on, and everyone I know pronounces these latter as though they rhymed with “supple.”

Defining and Using Tuples

Tuples are identical to lists in all respects, except for the following properties:

- Tuples are defined by enclosing the elements in parentheses (

()) instead of square brackets ([]). - Tuples are immutable.

Here is a short example showing a tuple definition, indexing, and slicing:

>>> t = (‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘)

>>> t

(‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘)

>>> t[0]

‘foo‘

>>> t[-1]

‘corge‘

>>> t[1::2]

(‘bar‘, ‘qux‘, ‘corge‘)

Never fear! Our favorite string and list reversal mechanism works for tuples as well:

>>> t[::-1]

(‘corge‘, ‘quux‘, ‘qux‘, ‘baz‘, ‘bar‘, ‘foo‘)

Note: Even though tuples are defined using parentheses, you still index and slice tuples using square brackets, just as for strings and lists.

Everything you’ve learned about lists—they are ordered, they can contain arbitrary objects, they can be indexed and sliced, they can be nested—is true of tuples as well. But they can’t be modified:

>>> t = (‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘, ‘quux‘, ‘corge‘)

>>> t[2] = ‘Bark!‘

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#65>", line 1, in <module>

t[2] = ‘Bark!‘

TypeError: ‘tuple‘ object does not support item assignment

Why use a tuple instead of a list?

-

Program execution is faster when manipulating a tuple than it is for the equivalent list. (This is probably not going to be noticeable when the list or tuple is small.)

-

Sometimes you don’t want data to be modified. If the values in the collection are meant to remain constant for the life of the program, using a tuple instead of a list guards against accidental modification.

-

There is another Python data type that you will encounter shortly called a dictionary, which requires as one of its components a value that is of an immutable type. A tuple can be used for this purpose, whereas a list can’t be.

In a Python REPL session, you can display the values of several objects simultaneously by entering them directly at the >>> prompt, separated by commas:

>>> a = ‘foo‘

>>> b = 42

>>> a, 3.14159, b

(‘foo‘, 3.14159, 42)

Python displays the response in parentheses because it is implicitly interpreting the input as a tuple.

There is one peculiarity regarding tuple definition that you should be aware of. There is no ambiguity when defining an empty tuple, nor one with two or more elements. Python knows you are defining a tuple:

>>> t = ()

>>> type(t)

<class ‘tuple‘>

>>> t = (1, 2)

>>> type(t)

<class ‘tuple‘>

>>> t = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

>>> type(t)

<class ‘tuple‘>

But what happens when you try to define a tuple with one item:

>>> t = (2)

>>> type(t)

<class ‘int‘>

Doh! Since parentheses are also used to define operator precedence in expressions, Python evaluates the expression (2) as simply the integer 2 and creates an int object. To tell Python that you really want to define a singleton tuple, include a trailing comma (,) just before the closing parenthesis:

>>> t = (2,)

>>> type(t)

<class ‘tuple‘>

>>> t[0]

2

>>> t[-1]

2

You probably won’t need to define a singleton tuple often, but there has to be a way.

When you display a singleton tuple, Python includes the comma, to remind you that it’s a tuple:

>>> print(t)

(2,)

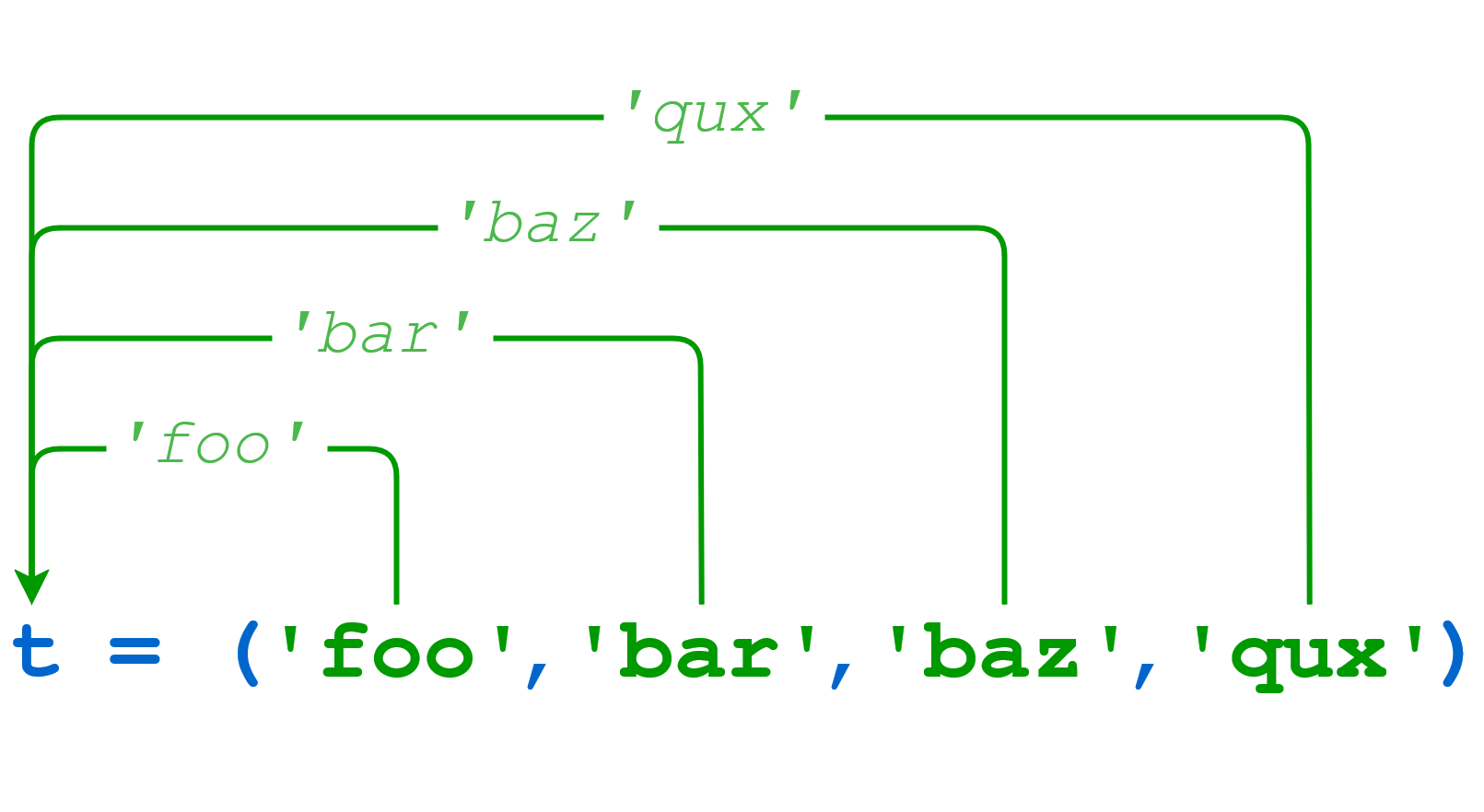

Tuple Assignment, Packing, and Unpacking

As you have already seen above, a literal tuple containing several items can be assigned to a single object:

>>> t = (‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘)

When this occurs, it is as though the items in the tuple have been “packed” into the object:

Tuple Packing

Tuple Packing

>>> t

(‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘)

>>> t[0]

‘foo‘

>>> t[-1]

‘qux‘

If that “packed” object is subsequently assigned to a new tuple, the individual items are “unpacked” into the objects in the tuple:

Tuple Unpacking

Tuple Unpacking

>>> (s1, s2, s3, s4) = t

>>> s1

‘foo‘

>>> s2

‘bar‘

>>> s3

‘baz‘

>>> s4

‘qux‘

When unpacking, the number of variables on the left must match the number of values in the tuple:

>>> (s1, s2, s3) = t

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#16>", line 1, in <module>

(s1, s2, s3) = t

ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 3)

>>> (s1, s2, s3, s4, s5) = t

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#17>", line 1, in <module>

(s1, s2, s3, s4, s5) = t

ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 5, got 4)

Packing and unpacking can be combined into one statement to make a compound assignment:

>>> (s1, s2, s3, s4) = (‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘)

>>> s1

‘foo‘

>>> s2

‘bar‘

>>> s3

‘baz‘

>>> s4

‘qux‘

Again, the number of elements in the tuple on the left of the assignment must equal the number on the right:

>>> (s1, s2, s3, s4, s5) = (‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#63>", line 1, in <module>

(s1, s2, s3, s4, s5) = (‘foo‘, ‘bar‘, ‘baz‘, ‘qux‘)

ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 5, got 4)

In assignments like this and a small handful of other situations, Python allows the parentheses that are usually used for denoting a tuple to be left out:

>>> t = 1, 2, 3

>>> t

(1, 2, 3)

>>> x1, x2, x3 = t

>>> x1, x2, x3

(1, 2, 3)

>>> x1, x2, x3 = 4, 5, 6

>>> x1, x2, x3

(4, 5, 6)

>>> t = 2,

>>> t

(2,)

It works the same whether the parentheses are included or not, so if you have any doubt as to whether they’re needed, go ahead and include them.

Tuple assignment allows for a curious bit of idiomatic Python. Frequently when programming, you have two variables whose values you need to swap. In most programming languages, it is necessary to store one of the values in a temporary variable while the swap occurs like this:

>>> a = ‘foo‘

>>> b = ‘bar‘

>>> a, b

(‘foo‘, ‘bar‘)

>>># We need to define a temp variable to accomplish the swap.

>>> temp = a

>>> a = b

>>> b = temp

>>> a, b

(‘bar‘, ‘foo‘)

In Python, the swap can be done with a single tuple assignment:

>>> a = ‘foo‘

>>> b = ‘bar‘

>>> a, b

(‘foo‘, ‘bar‘)

>>># Magic time!

>>> a, b = b, a

>>> a, b

(‘bar‘, ‘foo‘)

As anyone who has ever had to swap values using a temporary variable knows, being able to do it this way in Python is the pinnacle of modern technological achievement. It will never get better than this.

Conclusion

This tutorial covered the basic properties of Python lists and tuples, and how to manipulate them. You will use these extensively in your Python programming.

One of the chief characteristics of a list is that it is ordered. The order of the elements in a list is an intrinsic property of that list and does not change, unless the list itself is modified. (The same is true of tuples, except of course they can’t be modified.)

The next tutorial will introduce you to the Python dictionary: a composite data type that is unordered. Read on!