美杜莎之筏 The Raft of Medusa

Posted 送信人

tags:

篇首语:本文由小常识网(cha138.com)小编为大家整理,主要介绍了美杜莎之筏 The Raft of Medusa相关的知识,希望对你有一定的参考价值。

1816年,法国皇家海军的一艘护卫舰在试图殖民塞内加尔时遇难。大约有150名幸存者在这场海难中幸存下来,但经过13天的漫长等待,最终只有15人被“阿尔戈斯”号救起。其他人或者被杀、扔进大海,或者被饿死,或者因为绝望投海自杀。有4到5人在被阿耳戈斯号救起之后不治身亡。这件事是波旁王朝君主制的最大丑闻之一,与1815年拿破仑战败、波旁复辟等大事件相当。

这个故事的灵感也来自于法国浪漫主义画家雅各.路易.大卫的学生蒂奥多·杰里科(ThéodoreGéricault)的画作“美杜莎之筏”。蒂奥多·杰里科受好友德拉克罗瓦(Delacroix)著名画作《自由引导人民》的影响,以这一海难为原型,在没有任何订单的情况下,完全出于自发,用一幅巨画描绘了一个当代事件,开创了艺术创作的先河。该画与《自由引导人民》目前都馆藏于法国卢浮宫德农馆一楼莫里恩展厅77号展馆。

同时这个故事的创作手法也受到了丹.布朗的经典作品《达芬奇密码》的启发。最近刚刚完成了这本英文小说的阅读,宗教艺术与文学创作的完美结合,对于心灵是极大的震撼。我热爱艺术,热爱文字,对宗教也抱有浓厚的兴趣,《达芬奇密码》的创作手法让我有了许多新的想法。

我的小说结尾是在画家蒂奥多·杰里科(ThéodoreGéricault)的画室,他请来了年老的Pierre船长。Pierre船长当时已经患上了一种叫Kuru的疾病(Kuru曾经仅见于巴布亚—新几内亚东部高地有食用已故亲人脏器习俗的土著部落,自从这一习俗被废止后已无新发病例。库鲁病潜伏期长,自4—30年不等,起病隐匿,前期患者仅感头痛及关节疼痛,继之出现共济失调、震颤、不自主运动,在病程晚期出现进行性加重的痴呆,神经异常先后有震颤及共济失调后有痴呆是本病的临床特征。患者多在起病3~6个月内死亡。无法治疗。——来自《百度百科》)。Pierre坐在画室中,告诉了蒂奥多·杰里科发生在美杜莎之筏上的故事,画家就把这位老人Pierre画在了木筏上。

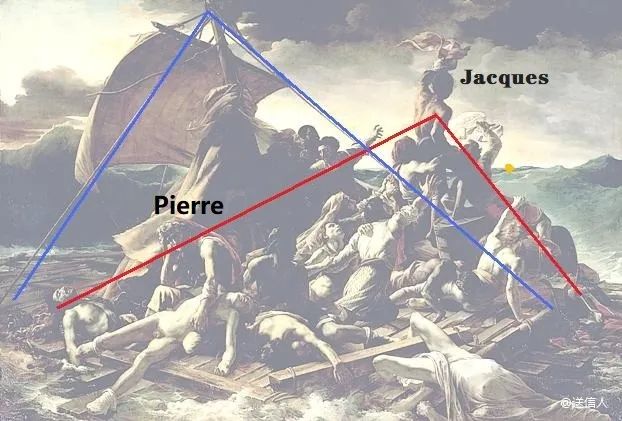

蒂奥多·杰里科把Jacques放在了美杜莎之筏的最上面,在我的小说里,Jacques就是那个踩在所有人之上,位于画面最高点,挥舞着红色布,棕皮肤的年轻人。而如果你顺着Jacques的背部线条往下看,他的左斜下方有一个披着红布的中年老人。这个中年老人与Jacques的头形成了一条斜线,这条斜线跟船帆的一条缆绳构成十字架。绘画作品《美杜莎之筏》在构图上采取了双金字塔结构。

所以,我的故事中Jacques在在金字塔的顶端,充满希望,充满活力,在向希望招手,而Pierre在金字塔的塔底,抱着一具尸体,独自哀伤。所以Pierre对画家说他和Jacques是两个非常不同的人,正如古罗马的神Janus的两个不同面孔,永远背对着彼此,看不到彼此。Pierre说Jacques他充满希望,他活力,他理想主义,而Pierre自己则非常功利,相当于是Pierre的自我剖白。画家绘画时,Pierre突然发病,当画家转身时,Pierre已经晕过去了,画家在Pierre的脚下发现了一个坏掉的锚(anchor)。锚在基督教中象征着希望,一个坏掉的锚则是无法弥补的希望。

以上的文字是妈妈把我发给她的微信语音转换成文字记录下来的,希望有人会喜欢我的英文作品与中文说明。

送信人:可人Keren

The Raft of the Medusa

The story is based on a real story. A French Royal Navy’s frigate had been crushed on the shore of Senegal in 1816 when it was trying to colonize the land. While around 150 survived the catastrophe, only fifteen managed to return to France on the brig Argus they waited for 15 days. The story is also inspired by the painting “The Raft of the Medusa” by the French Romantic painter Théodore Géricault.

Jacques was awaked by the coldness of the liquid on his face. He was lying on a massive raft with salty bodies placed around him, unconscious. Looking at his hand, his tanned skin is abnormally pale. The dark and thick clouds hung oppressively low in the sky he was facing; the built-up tension in the atmosphere indicated a coming storm. The violent feeling of the waves underneath him reminded him of the catastrophic shipwreck.

He was a helmsman on La Méduse heading toward Senegal to take the land away from the British control. With another four hundred people involving the politicians, new settlers, and some sailors in the frigate, La Méduse drove directly into a sandbank and encountered its doom—the tremendous shipwreck Jacques had ever experienced in his sailing career.

Then he was almost dead. Hit by a gigantic mast of the frigate, he must have fainted for hours. Jacques wiped his salty face and got up. The swirling feels still existed in the back of his head. He looked around. The raft was about 66 feet long and 23 feet wide. It was massive for a briefly constructed raft with a sail attached to a mast. The wooden edges of the raft were washed again and again by the black seawater, and the algae-covered boards were coming off.

There were about 150 people on the raft. Other than the few women who stayed on the raft edges, most of the men chose to remain near or in the middle of the raft for safety. Food shortages and dehydration spread visible anxiety among the survivors. People gathered in pairs or threes were sitting on different parts of the raft peeking at each other with doubtful and vigilant looks. There was a larger crowd of people gathering right in the middle of the raft. A crowd seemed to be arguing about something with another group of people. Jacques could not hear them, but he was sure about the anger. A moment later, he recognized a man he knew—Pierre, the 42 years-old chief mate of La Méduse.

Trying his best to ignore the dazzling in his head, Jacques got on his feet. As the raft creaked under the burden, he walked directly to the man. Pierre was the most familiar and trust-worthy man to him on this raft. The chief mate helped him a lot when he was working as a helmsman.

“Sir, why are we on a raft?” Stopped beside the chief mate, Jacques asked. Like all the other frigates, La Méduse had lifeboats just in case. People should be on the lifeboats for safety.

The middle-aged man drew himself out of the fierce argument and signed. His deep features seemed to fade under the dim light leaking out the gaps of the clouds.

“The viceroy took the lifeboats with the politicians and abandoned us; they should be on the shore of Mauritania by now.”

Jacques frowned. He decided not to speak about this topic. “What were you arguing then?”

The chief mate seemed even more unhappy now. Jacques doubted if it is the right topic to bring up. “The captain,” he said coldly, “is covered in wounds and is in a coma. I told them he could not live till tomorrow without proper medication. We were arguing who should be in charge of the whole raft during his coma.”

The man did not show much emotion toward the captain’s serious injury, but that was probably because he has never shown his feelings.

It was only after a moment that the sun sank below the horizon. With no idea of the time and the traumatic experience, most survivors chose to sleep, including Jacques.

* * *

The biological clock brought Jacques out of the dead sleep. The dense, black clouds hung even closer to the sea. Without any reason, the just-awaked helmsman realized the anger in the air. Dozens of survivors were all awaked now, gathering in the middle or near the centre of the raft, where the chief mate Pierre stood yesterday.

Jacques searched for the chief mate; the man stood right in the middle of the raft, speaking at a slow pace.

“As I told you, the captain died last night.” The chief mate looked around as if someone would challenge the fact, “he suffered exsanguination because of his wounds.”

A deadly silence fell. Thoughts and doubts of people were growing beneath the silence. The tension was visible.

“Is that all you wanted to tell us?” A fat and bald man suddenly questioned. He seemed like a politician but apparently failed to get on the lifeboat. “Is that the reason you called us up so early in the morning?”

“Sir, I beg your pardon.” Pierre said coldly as usual, “this is……”

“This is NOT important and NOT relevant to any other lives on this raft!” the man interrupted, shouting at the middle-aged chief mate.

“The people are starving and are lost on the sea. God knows where we are, and we cannot ask for help. You want to beg my pardon.” The man seemed even angrier now. His face was turning red. “Do we go back to France, or go to Senegal? Do we wait for death!?”

People around nodded for agreement; Jacques could hear people talking in small voices. The tense atmosphere needed only a match to break into war.

“Waking us up for bad news and its explanation only makes YOU look like a guilty murderer. Is it not you who murdered the captain for the power?

“The man in front of us is a traitor.”

Then all Jacques could remember is a long silence and a broken mutiny. The sailors were all on the chief mate’s side, but about twenty people were the man’s loyal followers. They are either settler of the new land or his fellow politicians. The sailors drove out their sailing knife and attacked the rebels while the rebels fight with fists. Sparkles of blood started to appear on the logs of the raft. The clamours of those fighting were deafening, and the whole picture was unrealistic yet realistic. People were dying. Jacques realized but the best thing to do in this situation was not to get involved. The flesh of the men was torn apart by the rusted sailing knives, layers of oily yellowish fat were exposed in the bloody air. When the last man fell, the chief mate surrounded by the sailors raised his blade and looked around again as he did at the start of this morning. He then cleaned his hands and started his speech again, as if all that just happened was a disappointing little accident.

“Gentlemen, I am no traitor, but this man…” he pointed to one of the bloody corpses, “he is. I promise to all a safe return.” His tone was slow but convincing. “My men and I will clean the raft in the next hour. Rest well.”

Jacques could barely feel his own legs as he sat down on the edge of the raft. His injury had gained him a chance to rest. The blood-coloured seawater was relentlessly washing the logs on edge. Layers of salts were left on the woods, for the water had evaporated. He did not want to speak to the chief mate. He trusted him, but he did not know if Pierre was correct at this point. Pierre was always correct. He told himself. The chief mate was always correct. Sitting on the edge of the raft, we could hear the sailors murmuring in French all the things just happened, the now-dead bald men, the hunger, and the bloodshed.

In a moment, he saw the vibrant gold light reflected by the gentle sway. The dawn started to materialize at the edge of the horizon. The dark, oppressive clouds were suddenly torn apart by the fierce beam of blinding light—a new day.

* * *

Jacques could only remember too well how the four days then passed. The weak and the injured were dying as the sun rises and sets. Storms and strong winds robbed the raft, leaving famine and terror living with the survivors. The carcasses of the dead were piled up at the verge of the raft, some broken limbs were soaking in the wine-coloured seawater. Around eighty were now found on the abandoned raft of La Méduse, desperate for auxiliary. Only sailors had food storage. The managers of the La Méduse and those who knew the sea well were now on the top of the hierarchy.

Jacques always considered himself as one of the sailors until he realized the source of the food.

About every evening, survivors on the raft would get a piece of dried, red meat distributed from the chief mate Pierre. The sailors, especially the chief mate, claimed that it was the dried beef brought from France as something the sailors could eat at night when they were still working. The people were grateful, but Jacques felt weird. As a young helmsman, he worked with his fellow helmsman together in rotations. Jacques would work at day, and his fellow would work at night. However, his fellow had never told him about the provided dry beef before. Neither had he heard it from the others.

Then it all came clear on the fifth morning on the raft.

It was another desperate morning with rays of sunshine piercing through the storms and clouds. Jacques was walking on the raft searching for the chief mate to ask if he should reef the temporary sail for the coming storm when he saw the chief mate with some high officials of the crew slicing the meat of the carcasses in smaller pieces and were trying to hang the meat onto the mast.

For twenty-one years, Jacques did not live stupid. He should have already doubted why the beef or veal tasted red meat was softer and sweeter than it should be. It was simply not beef, after all. It was the deads.

Ignoring the sudden feeling of vomit, Jacques moved his cold fingers and looked directly into the eyes of his chief mate. Tremors and terrors struck and devoured him. Sweats started to appear on his tanned skin. The sailor community was leading all the people on the raft; it was Pierre who was leading this community. The chief mate then responded to Jacques’ unspoken anger. His eyes were full of desperation and the sadness of a leader.

“Jacques.” The middle-aged man signed, “come here.” He watched Jacques as he walked and started to speak again. “You would die days ago without it.”

“I know.” Jacques responded softly.

“They would die days ago without it.”

The breath-taking silence fell. Jacques knew it was true yet the idea of eating his co-workers for four days is killing him. He looked helplessly at the man who was making all these things happen.

“Jacques.” The voice of the chief mate was lowerr now. “Jacques, remember how I helped you to become a helmsman? Help me for once. Keep the secret; I owe you forever.”

Jacques did not know what he was doing. Is it nobler to accomplish a just mission by an unjust mean? Or is it better to stop the just mission for an immoral mean? He barely had time to choose. Pick a side, Jacques. It is the best thing to do. After a long but invisible struggle, he nodded numbly at the chief mate and took a piece of meat for food.

The meat was kind of sweet and was soft even if it was dried.

* * *

It was the eighth day when everything went wrong. The carcasses started to rot and became inedible. The survivors were growing greedier and greedier and had to depend on the turtle’s blood and their own urine to get hydrated. At about five o’clock in the morning, just before the daybreak, the crew’s high officials were metting together to discuss the next step. The chief mate Pierre insisted on including Jacques, for he knew the secret.

Jacques was awaked by the gentile tap of the chief mate on his shoulders. With Pierre, Jacques moved silently to a corner of the raft as they planned.

The night is kind, for it covered all the secrets. Not a single survivor noticed the fifteen sailors on the edge of the raft. They had plenty of time to discuss what they should do.

The situation is serious. Everyone was clear that it was impossible for them to feed and support everyone who survived at this point. It is cruel but true. A successful mission needs sacrifice, and when no one wills to sacrifice, force and coercion are required.

Jacques had no idea of what these officials were thinking. To solve his confusion, he asked Pierre: “Sir, what are we going to do?”

Every present man was already sure what to do before the meeting. Instead of a meeting, it should probably be called a confirmation, a confirmation of bloodshed, a confirmation of willingness to be selfish and live, and a confirmation of willingness to bear the guilt forever.

* * *

On the 7th of July, the sea near Mauritania witnessed a massacre. The colour of oxidized blood dyed the water around in a wine colour. As the raft floated away, carnivores of the ocean gathered for the smell. Only fifteen men were left on the blood-dyed raft, fourteen of them tired and covered in wounds. They were all the officials of the old La Méduse crew. Their garments were soaked in the blood of the dead, and so did their hands.

However, there was one man standing at the edge of the blood-red raft. He stood there for a long time, but no one interrupted him. This man was about 20, and his tanned sweaty skin was reflecting the light from the rising sun. He was covered in blood and bruises, but he had no blood on his hand. He looked at the sea for a long time, then turned to the rising sun. It was strange, looking at the sun, Jacques thought. The sun is lighting the sky up, but the world is turning darker for me.

* * *

Water shortage filled the days with unspoken desperation. The vigilant officials doubted each other for the secret storage of food and water. The team of fifteen were in the middle of nowhere with endless waves surrounding them. The line of horizon briefly blended the Prussian blue sea and the cloud-covered sky together. While the fourteen were always discussing the next step they would take, Jacques spent most of his time at the edge of the fragile wooden structure, staring at the bottom of the bottomless sea. He knew more than anyone else that he stayed and survived the massacre because of the chief mate Pierre. If the chief mate did not ask the officials to spare his life, the crew would most probably contain fourteen people instead of fifteen.

It was the fifteenth day on the sea. Jacques and the officials had finished the last slice of meat, and some even fainted because of dehydration. The crew of fifteen peered at the horizon, as usual, to look for passing ships, but in vain. Everyone was on the verge of giving up. The sailors tried every method to survive.

Jacques felt the hunger growing in him. His stomach was growling, complaining about the little food it got in the last three days. His limbs were shimmering for the lack of energy. He was constantly dizzy and sleepy. He moved his body to the edge of the raft and sat down. Beside him was a pile of rotten corpses, above him a storm-producing sky, below him a fragile wooden structure and a cruel yet beautiful sea he had worked with for years.

Watching the waves passing, the helmsman almost fell asleep when, though it might be an illusion, he saw a sail on the edge of the horizon. Human beings! His mind cried. Forcing his eyes to open, he was not mistaken. It was a brig.

As the double-masted sailing boat approaches. Fire lit up Jacques’s head all of a sudden.

“Attention!” Jacques shouted to all the officials as he climbed up the pile of corpses, “Attention! Chief mate Pierre, everyone, I saw a brig!!!”

As Jacques shouted, all the officials gathered near the pile of dead surrounding Jacques. A man tightened the sail so the raft would move slightly forward. The tired survivors raised their arms and waved them in the air, trying to catch their last glimpse of the chance. The storms were roaring now. The deafening sound was a torture to the human ears. The waves were growing higher and higher, almost burying the abandoned raft of La Méduse, but nobody cared. The desperate people were shouting and screaming in chaos, trying their best to cover the gigantic cacophony of storms and nature. Jacques tore up his red-brownish garment and waved it in the salty sea air. He almost fell off the little mountain of corpses as he waved. Then, he felt the officials at his back supporting him and tried to raise him higher. This is our last hope. Jacques thought. And we are over.

He reached his arm high to the sky, waving the garment, again and again, using his last effort.

* * *

In his studio, Géricault rinsed his paintbrushes. He had just decided to pause the picture on this breath-taking moment of fake hope. According to the story provided by the chief mate Pierre now sitting in his studio, the brig Argus did not see and save the fifteen until a few hours later. Argus was too far away to see the young Jacques waving his red garments at this point. It was two years from the actual shipwreck, yet Pierre could remember every detail of this fifteen-day odyssey. The chief mate was still a middle-aged man, but he looked much older. His deeply featured face, now covered by scars, wrinkles, and blemishes. With his messy grey hair, he seemed tired and old. The man now suffers kuru, a disease caused by the mutated proteins (prions) in the human brain. He was infected probably because of the cannibal deeds he had done on the raft, yet no one was sure. The chief mate now frequently suffers muscle twitches and became very uncoordinated, which stopped him from being a sailor.

Looking at the chief mate, the young painter remained still for a while. Then he quietly mixed a new skin tone on his palette and painted a grey-haired man on the opposite side of Jacques in his painting. The two men face opposite directions, on the top right of the picture, the brown-skinned young man facing the frig Argus and the sea, reaching out his hand waving a red cloth. In contrast, the chief mate sat at the bottom left of the painting, looking down at the raft with a corpse in his arm; he seems old and tired, his eyes looking aimlessly at the rotted logs beneath. As one looking up, the other looks down; as one facing the sea, one faces the raft of rotted wood, for Géricault had heard the ill man murmuring at the corner of the studio and signed:

“Jacques and I are different. He is young, brave, strong, kind, and hopeful; I am old, coward, weak, and utilitarian. We are like the two faces of Janus.”

Finished the overall shape of the last figure, Géricault turned and looked at the chief mate. The man’s body muscles started to twitch violently, a symptom of kuru. The young painter watched the chief mate twitching for a long time without a word and waited till the chief mate’s symptom completely stopped.

The painter turned around.

He rinsed the brush again and added the details to the figure of the sitting man, according to the features of the chief mate. The middle-aged man is now silent. He has probably fainted.

At his feet, laid a broken anchor.

END

为梦想码字,欢迎打赏!

以上是关于美杜莎之筏 The Raft of Medusa的主要内容,如果未能解决你的问题,请参考以下文章