Experiencing the Great American Eclipse

Posted 石头科普工作室

tags:

篇首语:本文由小常识网(cha138.com)小编为大家整理,主要介绍了Experiencing the Great American Eclipse相关的知识,希望对你有一定的参考价值。

FIVE. FOUR. THREE. TWO. ONE –The last peeking rays of sunlight suddenly dimmed as the sky transformed,taking on an ethereal glow. As the river of sunlight diminished to a trickleand the trickle to drops, none of the change compared to the instant the goldenstream ran dry.

Although solar eclipses aren’t rare, neither are they a frequent occurrence, especially in recent history ofthe United States where the last eclipse to pass across the country was almost 100 years ago. And since then, the world has become a much more connected place. When the sudden dimming of the sun may have come as a surprise to people100 years ago, this eclipse would be one of the most anticipated natural eventsin history. Not only would people be gathering to witness the celestial eventbut to also take advantage of the opportunity to make scientific observations.These observations could improve our understanding of our sun and what a suddenreduction in sunlight has on our planet’s atmosphere and the conditions at thesurface. During the day of August 21st, 2017, universities acrossthe United States, along with NASA, NOAA, and hobbyists like myself madeobservations beneath the moon’s shadow from one end of its path to the other.The sun, the single most important component for life on earth, would be cutoff for just a few minutes. What would the effects be? How would the atmosphere and its layers respond? How would life itself react to sudden night in themiddle of the day?

Attending graduateschool at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, I couldn’t pass the opportunityto take a short drive north to experience totality. Knowing that masses ofpeople would be traveling to the same area, I grabbed my camping gear andheaded to the most remote place I could find on the map. Even though I would bewatching from Wyoming, the least populous state in the U.S., I still felt itnecessary to head up a day early. My quest for a remote area led me to a regionof the Medicine Bow National Forest in eastern Wyoming and, upon arriving, itwas still a surprise to find about a hundred people with tents already set up,staking out their precious piece of land. Finding our own flat spot along therutted and rocky road, my friend Lin and I set up camp. Then, it was time to kill time.

location

In the meantime, I had a few things to prepare if I wanted to make the most of the event. Accompanying me on the adventure was my trusted Nikon Coolpix camera with three batteries (just in case). It’s small enough for easy packing yet has enough features to take some great shots. Set-up was a breeze as I picked a shaded spot at the side of an aromatic pine tree and deployed my tripod. Second to my camera was a brand-new personal weather station. Again, nothing fancy (college student budget you realize) but equipped to measure all the basics (temperature, humidity, wind speed, pressure) and send it wirelessly to a readout panel. I mounted the instrument package on a PVC pipe, about a meter tall, which was then wedged into the crack of a boulder tight enough so that any wind that came up wouldn’t move it. With the camera and weather station both ready and operational, preparation was over and the countdown was on.

equipment

The next morning arrived andthe sun rose into the sky right where it normally does this time of year justas if it was a normal day. We awoke to obnoxiously loud clicking grasshoppersand chattering birds who were unaware of the coming celestial alignment. Theconditions were perfect for viewing an eclipse; only a light breeze blew and therewasn’t a cloud in the sky. After a seemingly eternal wait and occasionalglances at the sun through our filtered glasses, it finally began. Almostimperceptibly at first, a small dent in the solar disk became more apparent asthe seconds ticked by. There was no easily discernable indicator that the moonwas to blame, only a curved region of the sun seemed to be missing. Like aperson slowly taking larger and larger bites out of a radiating cookie. To Linand me, no differences could be felt or seen around us until maybe a third ofthe sun was blocked. I had been alternating between my sunglasses and eclipseglasses until I suddenly decided that my sunglasses were no longer necessary.The usually bright glare from the sun in the sky and on the surroundinglandscape had dimmed considerably. Also, the temperature, which had risenquickly from low of 50°F (10.0°C) to 73°F (22.8°C) suddenly stopped rising. Thewarmth of the sun usually felt on exposed skin was no longer perceptible. Asthe eclipse moved closer to totality, the temperature began to plummet withsurprising quickness. Lin donned her jacket but I am stubborn and wasdetermined to experience the temperature swing to its fullness. Throughout themorning, a weak although persistent northeasterly wind had been blowing. As theshadow approached our position from the northwest, the wind direction shiftedto be from the north. When there were only a few minutes left until totality,rapid changes began to occur. The temperature continued to drop, grasshoppersand birds became quieter, and the sky began to change color to an eerie darkgray, blue color.

FIVE. FOUR. THREE. TWO. ONE – It’s incredible the difference just a little bit of sunlight makes. For a moment there were just a few bright spots, like shining pearls on a necklace, and then they were gone. Totality. Total Quiet. Total stillness. Total awesomeness. All kinds of life went quiet. There were no more obnoxious clicking grasshoppers and no more chirping birds. Even a bat appeared to hunt in the midday night. Also, the wind completely died. While minutes ago there was still sun rays falling on the forest of pine trees, they now stood as dark shadows. Yet, the most incredible thing of all, when the sun’s disk became entirely covered, a bright ring lit up around it. The sun’s corona was suddenly visible appearing like bright streamers in the dark sky. In the surrounding sky a few bright stars became visible along with the planets Venus and Mercury. Exactly two minutes of totality and it was totally worth it. After a few rushed pictures, a few written observations, and a moment or two just to take in the otherworldliness, the total eclipse was over. With only a tiny bit of the sun visible again, the temperature still dropped a few more degrees, bottoming out at 58°F (14.4°C) as it slowly pulled out of its dive. Estimates before the eclipse suggested as much as a 10°F (5.6°C) drop in temperature so it was an exciting surprise to measure a 15°F (8.4°C) drop! As the moon’s shadow passed to our east, a breeze suddenly sprang up out of the cooler, denser air in the shadow. It was an ‘eclipse wind’ where air flowed from higher pressure within the shadow to lower pressure in the surrounding warmer air. Like the slowly rising temperature, the grasshoppers and birds slowly resumed their conversations with one another. The first half of the eclipse now began to move in reverse and the sun incrementally regained its normal size in the sky. After two hours and forty-seven minutes, the sun and moon parted ways and the eclipse was over. Until next time, that is, which would only be a little over six years away, and I’ll be ready.

the eclipse

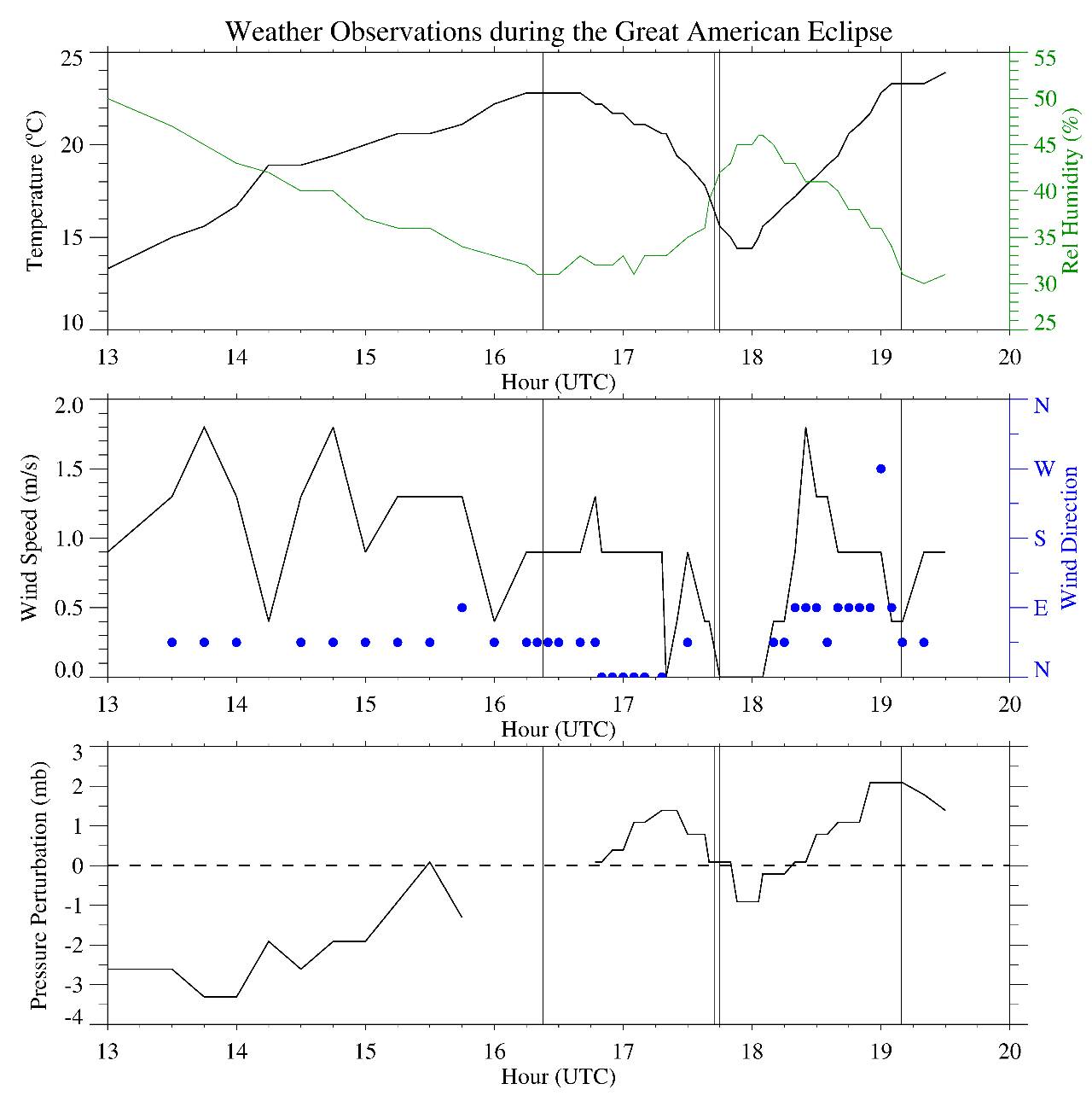

The following graphs show the data collected by Lin Lin and me during the eclipse. From top to bottom: temperature (black) and relative humidity (green), wind speed (black) and wind direction (blue), and pressure perturbations. Vertical lines indicate the start of the partial eclipse, start of the total eclipse, end of the total eclipse, and end of the partial eclipse respectively. Instantaneous wind direction was estimated at the time of each observation using a compass bearing. Some pressure measurements were excluded because it was later discovered that the readout panel housed the barometer which temporarily became exposed to sunlight and heated up giving inaccurate values. Pressure perturbation is the mean pressure subtracted from the actual pressure measurements.

The morning temperature reaches a maximum at the beginning of the partial eclipse when solar radiationis reduced. At 16:47 UTC, thermal radiation from the surface becomes greater than the energy received from the sun, cooling the surface. The lowest temperature occurs 8 minutes after the total eclipse after the sun has begun to re-emerge.It takes another 10 minutes until the radiation from the sun becomes greaterthan the cooling so that the surface temperature begins to rise again. Relative humidity is relative to the amount of moisture in the air AND temperature.During the short period of observations there were no events to significantly change the amount of moisture in the air. Because of this, the change inrelative humidity reflects the change in temperature (although they areinversely related).

The high pressure during theeclipse and weak winds were ideal for measuring any effects the eclipse had onthe wind. In theory, the coolest temperatures within the shadow should beco-located with measurements of the highest pressure (refer to hydrostatictheory). In perfect conditions, this should result in windblowing from the shadow in all directions. The synoptic (or large-scale)pressure distribution drove the small northeasterly wind measured before 16:50.At this time, the theorized high pressure beneath the shadow neared ourposition and can explain the shift in wind direction to a more northerlycomponent. When the total eclipse and ‘bubble’ of higher pressure moved overhead, the wind becomes calm as wouldbe expected. After the shadow passes, theory holds when the wind returns, now,from east (out of the shadow). Within an hour, the wind becomes barelymeasurable and variable, even briefly coming out of the west.

The last panel display spressure perturbations. These perturbations do not match with the theory discussed in the discussion of the wind. In fact, they are closer to the exactopposite. This inconsistency may be a result of synoptic changes being more dominant than effects of the eclipse or simple equipment error. Even so,similar pressure observations have been published (e.g. Anderson et al.)[1]Although a conundrum, it is motivating to know that a mystery survived thisanalysis and that the next solar eclipse could, ironically, provide some additional light.

The Author

Coltin Grasmick

My name is Coltin Grasmick and I am a graduate student at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming, United States. I grew up in a rural, agricultural community along the Arkansas River in Colorado enjoying wide-open spaces and outdoor adventures. From hard work in the field, to hunting and fishing, there was never a dull moment. At a young age, I became fascinated with the weather. Southeast Colorado experiences a large variety of weather from blizzards in the winter, to severe storms in the summer. After graduating high school, I moved to Greeley, Colorado to study earth science and meteorology at the University of Northern Colorado. I finished up my undergraduate degree and am continuing my education here as a masters and Ph.d student in the department of atmospheric science. When I’m not working on my research or class work, I am often exploring the nearby mountains, fishing, skiing, or taking pictures of something with my camera.

reference:

[1]Anderson, R. C., D. R. Keefer, and O.E. Myers, 1972: Atmospheric Pressure and Temperature Changes During the 7 March1970 Solar Eclipse. J.Atmos.Sci., 29, 583-587, doi:APATCD>2.0.CO;2.

撰文:Coltin Grasmick

美编:雷霆

责编:许可

石头科普工作室出品,转载请注明出处

投稿邮箱:dr.stone@ustc.edu.cn

以上是关于Experiencing the Great American Eclipse的主要内容,如果未能解决你的问题,请参考以下文章