进程间通信——管道

Posted WoLannnnn

tags:

篇首语:本文由小常识网(cha138.com)小编为大家整理,主要介绍了进程间通信——管道相关的知识,希望对你有一定的参考价值。

文章目录

进程间通信介绍

进程间通信目的

- 数据传输:一个进程需要将它的数据发送给另一个进程

- 资源共享:多个进程之间共享同样的资源。

- 通知事件:一个进程需要向另一个或一组进程发送消息,通知它(它们)发生了某种事件(如进程终止时要通知父进程)。

- 进程控制:有些进程希望完全控制另一个进程的执行(如Debug进程),此时控制进程希望能够拦截另一个进程的所有陷入和异常,并能够及时知道它的状态改变。

进程间通信发展

- 管道

- System V进程间通信

- POSIX进程间通信

进程间通信分类

管道

- 匿名管道pipe

- 命名管道

System V IPC

- System V 消息队列

- System V 共享内存

- System V 信号量

POSIX IPC

- 消息队列

- 共享内存

- 信号量

- 互斥量

- 条件变量

- 读写锁

要让两个不同的进程实现通信,前提是让这两个进程看到同一份资源

管道

什么是管道

- 管道是Unix中最古老的进程间通信的形式。

- 我们把从一个进程连接到另一个进程的一个数据流称为一个“管道 ”

匿名管道

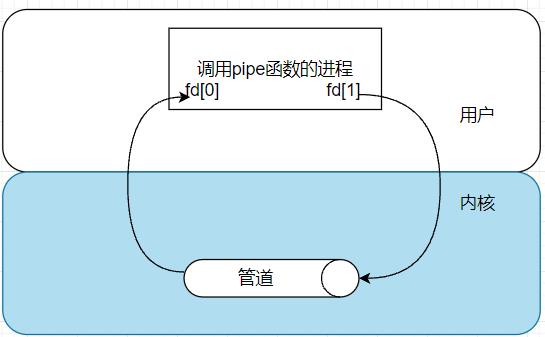

#include <unistd.h>

功能:创建一个无名管道

函数原型

int pipe(int fd[2]);

参数

fd:文件描述符数组,其中fd[0]表示读端, fd[1]表示写端

返回值:成功返回0,失败返回-1

实例代码

//例子:从键盘读取数据,写入管道,读取管道,写到屏幕

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main( void )

int fds[2];

char buf[100];

int len;

if ( pipe(fds) == -1 )//创建匿名管道

perror("make pipe"),exit(1);

// read from stdin

while ( fgets(buf, 100, stdin) ) //循环向buf中写数据

len = strlen(buf);

// write into pipe

//先写再判断

if (write(fds[1], buf, len) != len) //当实际写入管道的字符个数不等于buf长度时,就写入错误

perror("write to pipe");

break;

memset(buf, 0x00, sizeof(buf));//将buf的内容置为0

// read from pipe

if ( (len=read(fds[0], buf, 100)) == -1 ) //先读再判断

perror("read from pipe");

break;

// write to stdout

if ( write(1, buf, len) != len ) //先写再判断

perror("write to stdout");

break;

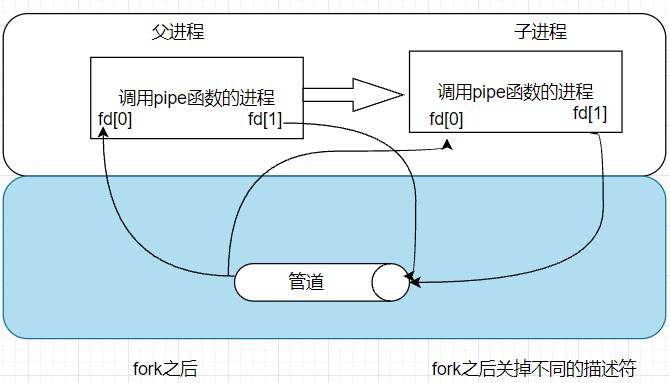

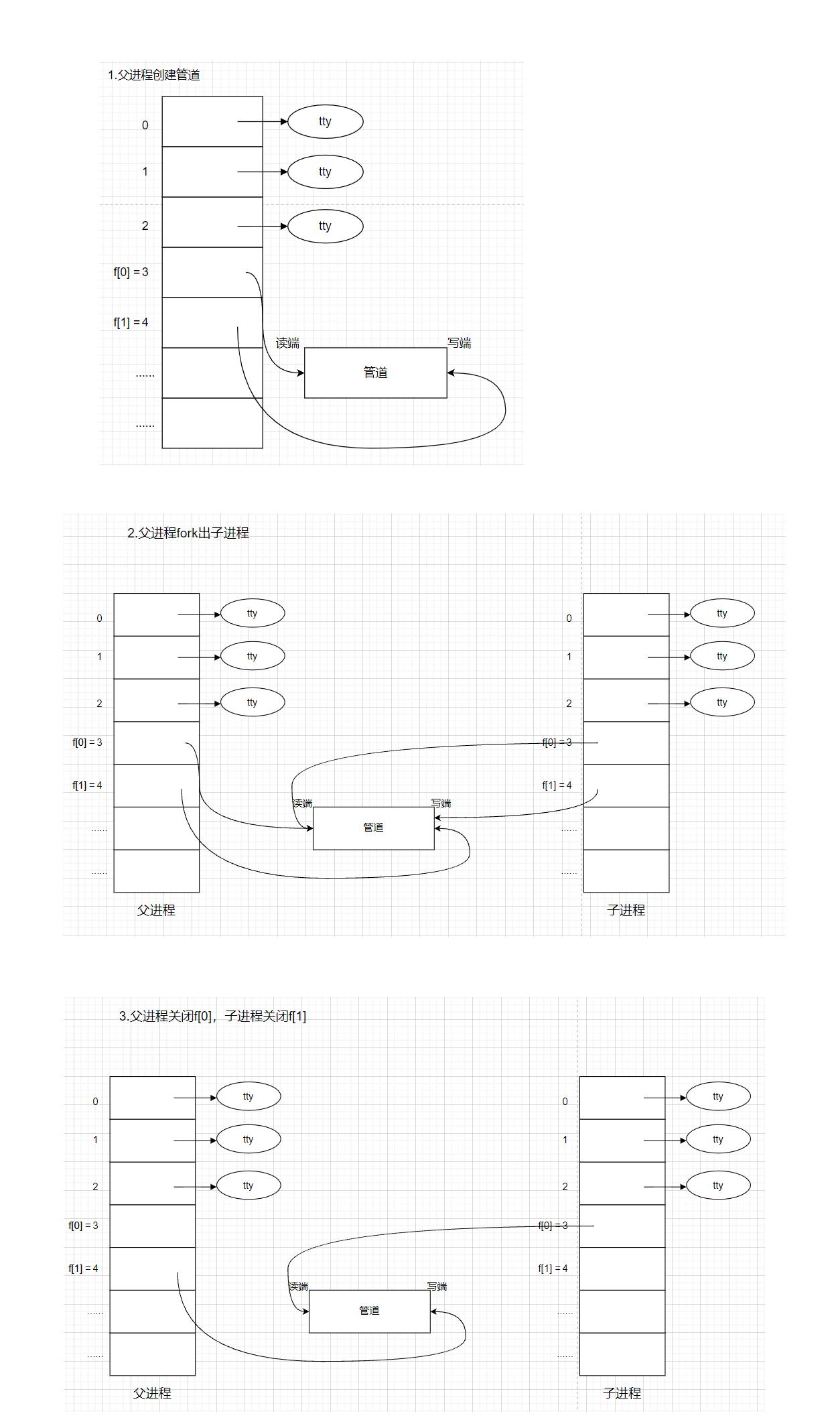

用fork来共享管道原理

站在文件描述符角度-深度理解管道

因为我们最开始的进程打开了标准输入、标准输出、标准错误三个文件,所以之后所有的进程都默认打开这三个文件

为什么文件不会各自私有?因为文件是不属于进程的

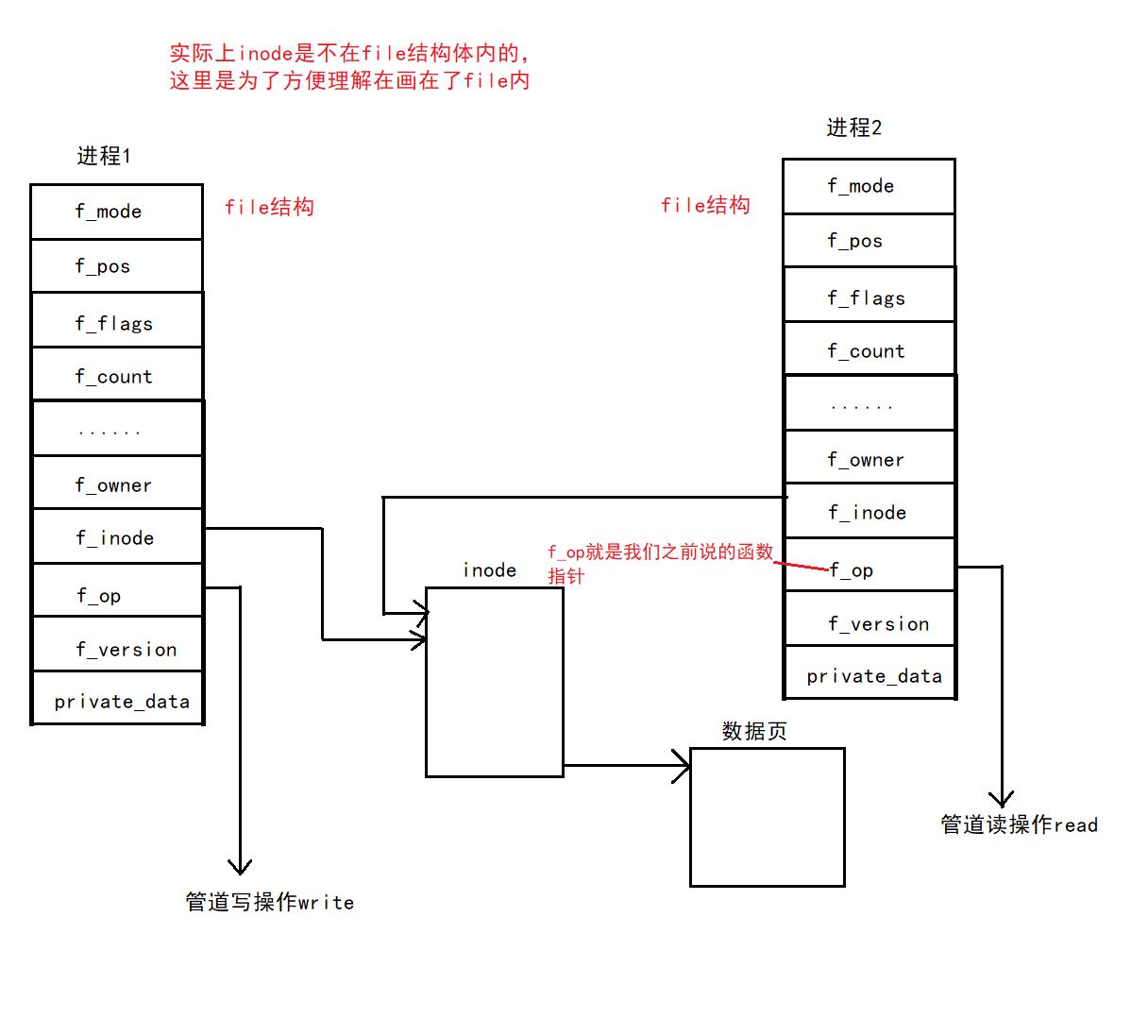

站在内核角度-管道本质

f_op就是我们之前说的函数指针。

图是简化理解的,inode指针并不在struct file中

所以,看待管道,就如同看待文件一样!管道的使用和文件一致,迎合了“Linux一切皆文件思想” 。

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#define ERR_EXIT(m) \\ do \\ \\ perror(m); \\ exit(EXIT_FAILURE); \\ while(0)

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

int pipefd[2];

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1)

ERR_EXIT("pipe error");

pid_t pid;

pid = fork();

if (pid == -1)

ERR_EXIT("fork error");

if (pid == 0) //子进程

close(pipefd[0]);//关闭读端

//向管道写入

write(pipefd[1], "hello", 5);

//关闭写端,减少文件描述符的占用

close(pipefd[1]);

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

//父进程关闭写端

close(pipefd[1]);

char buf[10] = 0;

//从管道中读数据

read(pipefd[0], buf, 10);

printf("buf=%s\\n", buf);

return 0;

管道读写规则

-

如果写端不关闭文件描述符,也不写入,读端可能会阻塞很长时间(可能管道中一开始就有数据,不会立马就阻塞)

示例:

#include<stdio.h> #include <unistd.h> #include<string.h> int main() int pi[2] = 0; if (pipe(pi) < 0)//创建匿名管道失败 perror("pipe"); return 1; int pid = fork(); if (pid < 0) perror("fork"); return 1; //让子进程写,父进程读 if (pid == 0)//子进程 //怕失误使用了另一个接口,所以关闭子进程的读 close(pi[0]); const char* buf = "I am a child!\\n"; while (1) write(pi[1], buf, strlen(buf)); sleep(3);//子进程每隔3s才写入 else//父进程,只读 close(pi[1]); char buf[64]; while (1) ssize_t s = read(pi[0], buf, sizeof(buf) - 1); if (s > 0) buf[s] = 0; printf("father get info from pipe:%s\\n", buf); return 0;因为子进程每隔3s才写入管道,而父进程则是无间断地读取管道数据,所以相对来说父进程会阻塞一段时间:

所以,如果我们关闭了子进程的文件描述符,父进程就会一直在等待,也就是陷入长时间的阻塞。

-

当我们写入时,如果写入条件不满足(管道满了,读端读取速度太慢),写入端就会阻塞

#include<stdio.h> #include <unistd.h> #include<string.h> int main() int pi[2] = 0; if (pipe(pi) < 0)//创建匿名管道失败 perror("pipe"); return 1; int pid = fork(); if (pid < 0) perror("fork"); return 1; //让子进程写,父进程读 if (pid == 0)//子进程 //怕失误使用了另一个接口,所以关闭子进程的读 close(pi[0]); const char* buf = "I am a child!\\n"; int count = 0; while (1) write(pi[1], buf, strlen(buf)); printf("CHILD:%d\\n", count++); else//父进程,只读 close(pi[1]); char buf[64]; while (1) ssize_t s = read(pi[0], buf, sizeof(buf) - 1); sleep(1);//父进程每隔1s读一次 if (s > 0) buf[s] = 0; printf("father get info from pipe:%s\\n", buf); return 0;可以看到,子进程一开始就在猛地写入,而父进程每隔1s才读一次数据,并且从父进程开始读数据,子进程就没有再写入了,是因为管道满了,写入条件不满足,无法完成写入。

-

如果写端关闭文件描述符,读端在读取管道时会读到0,也就是read函数返回0

#include<stdio.h> #include <unistd.h> #include<string.h> int main() int pi[2] = 0; if (pipe(pi) < 0)//创建匿名管道失败 perror("pipe"); return 1; int pid = fork(); if (pid < 0) perror("fork"); return 1; //让子进程写,父进程读 if (pid == 0)//子进程 //怕失误使用了另一个接口,所以关闭子进程的读 close(pi[0]); const char* buf = "I am a child!\\n"; int count = 0; while (1) if (count == 5)//子进程只写入5次 close(pi[1]); write(pi[1], buf, strlen(buf)); ++count; else//父进程,只读 close(pi[1]); char buf[64]; while (1) ssize_t s = read(pi[0], buf, sizeof(buf) - 1); sleep(1);//父进程休眠1s再读取 if (s > 0) buf[s] = 0; printf("father get info from pipe:%s\\n", buf); printf("father exit return : %d\\n", s); return 0;子进程无休眠地只写入5次,而父进程休眠1s读取一次,当子进程停止写入后,父进程从管道中读取的数据就为0了。

-

如果读端关闭,写端进程可能直接被杀掉

#include<stdio.h> #include <unistd.h> #include<string.h> #include<stdilb.h> int main() int pi[2] = 0; if (pipe(pi) < 0)//创建匿名管道失败 perror("pipe"); return 1; int pid = fork(); if (pid < 0) perror("fork"); return 1; //让子进程写,父进程读 if (pid == 0)//子进程 //怕失误使用了另一个接口,所以关闭子进程的读 close(pi[0]); const char* buf = "I am a child!\\n"; int count = 0; while (1) write(pi[1], buf, strlen(buf)); printf("CHILD:%d\\n", count++); exit(2); else//父进程,只读 close(pi[1]); char buf[64]; int count = 0; while (1) if (5 == count++) close(pi[0]); break; ssize_t s = read(pi[0], buf, sizeof(buf) - 1); sleep(1); if (s > 0) buf[s] = 0; printf("father get info from pipe:%s\\n", buf); return 0;初步观察:

我们看到在父进程读取5次后,父子进程都结束了,子进程也没有继续打印了,而是退出了。

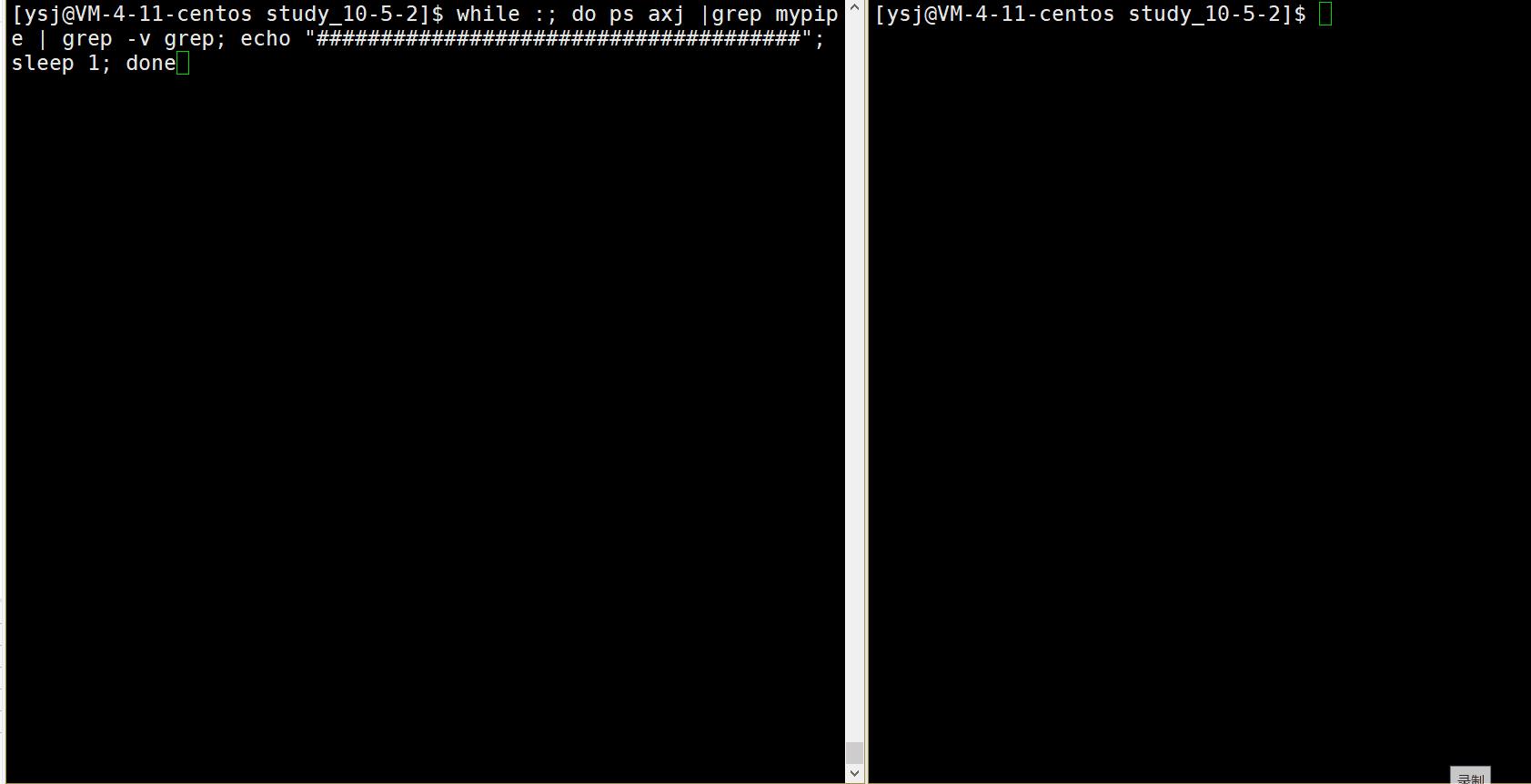

我们不让父进程结束,再来用脚本来观察父子进程的状态:

shell脚本:

while :; do ps axj |grep mypipe | grep -v grep; echo "######################################"; sleep 1; done

效果:

可以看到实际上子进程是处于僵尸状态了,也就是退出了。

实际上,它是被操作系统杀掉了,因为管道里面已经没人读数据了,而子进程还往管道里面写数据是在浪费资源,操作系统不允许这种行为发生,于是,就杀掉了子进程。

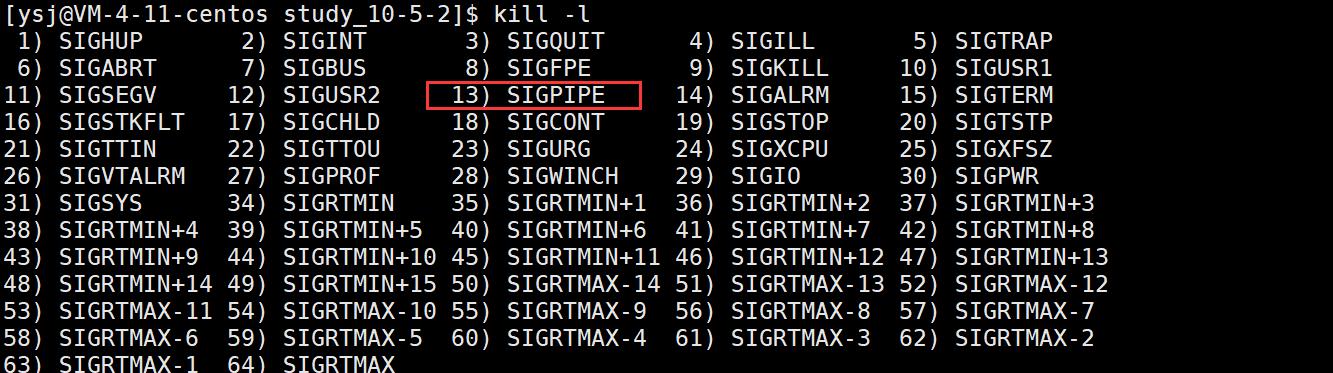

既然子进程是被杀掉的,就需要用父进程回收,并且获取它的信号

修改一下代码,让父进程等待,并且获取信号:

可以看到子进程的退出信号是13

我们使用kill -l查看一下kill的13号命令:

顾名思义,该信号是用来杀死管道相关的进程的。

修改代码:

#include<stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<sys/wait.h>

int main()

int pi[2] = 0;

if (pipe(pi) < 0)//创建匿名管道失败

perror("pipe");

return 1;

int pid = fork();

if (pid < 0)

perror("fork");

return 1;

//让子进程写,父进程读

if (pid == 0)//子进程

//怕失误使用了另一个接口,所以关闭子进程的读

close(pi[0]);

const char* buf = "I am a child!\\n";

int count = 0;

while (1)

write(pi[1], buf, strlen(buf));

printf("CHILD:%d\\n", count++);

exit(2);

else//父进程,只读

close(pi[1]);

char buf[64];

int count = 0;

while (1)

if (5 == count++)

close(pi[0]);

break;

ssize_t以上是关于进程间通信——管道的主要内容,如果未能解决你的问题,请参考以下文章